A rain jacket is one of the first pieces of performance outdoor equipment many outdoor enthusiasts purchase. The primary reason is that a waterproof shell is among the most important pieces of gear for comfort and safety when a storm rolls in or the wind starts to howl. The models tested in our rain jacket review span affordable rain protection options for day hikes and general around-town use, as well as ultralight rain protection for climbing, long-distance backpacking, and trail running. Whether you're searching for your first jacket, a modern replacement for an old favorite, or an ultralight model to add to your quiver, you're in the right place.

Construction 101: 2, 2.5, and 3-layer Fabrics

Nearly every manufacturer clearly lists how many layers their jacket is constructed with, but if you're like many people, you've likely wondered, What does that even mean? Are more layers better? Worse? What are the pros and cons of each, and most importantly, how should this affect what products you consider?

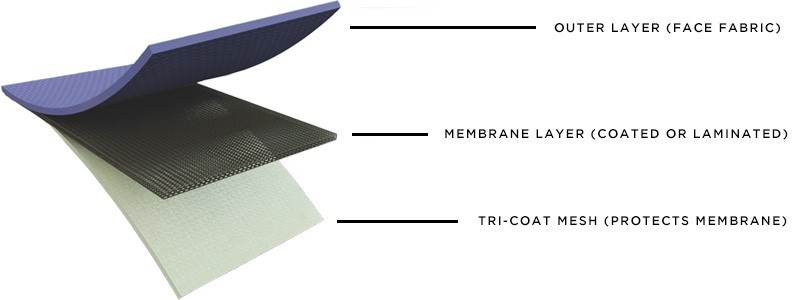

Most rain shell fabrics use a 2, 2.5, and 3-layer construction, even though nearly all of them only look like a single layer when you hold them at the store because these layers are tightly-sandwiched and laminated together. Whether a 2, 2.5, or 3-layer fabric, these designs share most of their construction qualities, with only a small difference generally presenting on the inside facing side of the garment. All three styles feature an outer shell fabric, commonly referred to as a face fabric, which is coated with a chemical Durable Water Repellent (AKA: DWR, more on this below) finish to help keep the outer layer from absorbing water.

The second, or middle layer, is the actual waterproof layer, whether eVent, Gore-Tex, another proprietary membrane generally made of polyester or nylon, or a coated fabric.

3-Layer Fabrics

Three-layer builds feature an external DWR-treated face fabric with a waterproof, breathable membrane in the middle (that could be any of the types listed above), in addition to a super-thin polyurethane (PU) film or other similar backing on the inside of the product. The goal of the third layer is to keep sweat and oils from clogging the microscopic holes in the waterproof-breathable layer. This reduces breathability and will likely make the user feel wet from sweat, that they might think is coming from the outside.

The advantage of a three-layer build is that they are typically the most durable because the innermost layer, which protects the waterproof membrane's pores from clogging (at least for longer), thus maintaining better breathability between washings. The disadvantage of three-layer pieces is that they are not always as breathable and are often slightly heavier than many of their 2 or 2.5 layer counterparts.

2.5-Layer Fabrics

Outerwear with a 2.5 layer construction looks similar to those with a three-layer design but may feel slightly lighter in hand. Jackets made of a 2.5 layer material still have the same outermost layer (the face fabric) treated with DWR, which minimizes how much water is absorbed by encouraging moisture to shed, thus helping to protect the waterproof layer below. A “middle” waterproof layer applies as well. However, in the case of three-layer builds, this can be anything from an ePTFE membrane to a coated piece of nylon. In contrast, in 2.5-layer jackets, it is generally a treatment that's “painted on” instead. This is why it's considered a half layer (yes, the painted on layer is the half-layer), even if it covers all of the inside surface area. Such a strategy makes for a much thinner and lightweight result than what most 3-layer garments can offer.

Jackets with a 2.5 layer construction also offer similar degrees of breathability to what is seen in 3-layer jackets, though they may occasionally feel marginally clammier, depending on the innermost lining fabric. Why? The innermost layer doesn't do quite as good of a job at “absorbing” and transferring sweat compared to the innermost lining fabric featured on most three-layer models. 2.5-layer jackets are typically slightly lighter and more packable, but often are not quite as durable (and must be cleaned more frequently to maintain a similar level of breathability). It is worth noting that this portion of the market has grown substantially over the past few years, showing more updates and improvement in design. Some 2.5 layer jackets now deliver a far less clammy experience than what was notable in earlier iterations.

2-Layer Fabrics

There has been a big change in 2-layer fabrics in the last year or two. Traditionally, 2-layer products would have the same DWR face fabric bonded to a waterproof-breathable layer but include a loose (typically mesh) liner hanging on the inside. This style fell out of favor as 2.5-layer models became more affordable, and 2-layer garments with their hanging mesh liner were heavier, bulkier, and generally less comfortable.

Recently Gore-Tex has re-introduced a 2-layer design in the form of Gore-Tex Paclite Plus. Paclite Plus has the same exterior face fabric laminated to a waterproof membrane. Still, instead of a laminated layer (like a 3-layer) or spraying on a protective coating (like a 2.5-layer) Gore has instead textured the inside of the waterproof membrane in such a way to increase its abrasion resistance, rendering a half-layer treatment or full third layer unnecessary. Sticking with only two layers means that such a garment is more breathable than many, as moisture has less fabric to travel through. It also reduces overall weight due to the decrease in materials. It's worth noting that Paclite Plus is made of a different construction than the older Gore Paclite, which used a traditional 2.5-layer construction. Other 2-layer materials may not yet claim the same performance upgrades.

Waterproof Membrane Types

ePTFE Fabrics:

Gore-Tex is an ePTFE waterproof-breathable fabric that is the oldest and most widely known and has become somewhat of the Kleenex of the waterproof-breathable fabric world. On a fundamental level, Gore-Tex is a polytetrafluoroethylene (or ePTFE for short) membrane stretched to a specific dimension. At this dimension, water vapor can escape. Still, liquid water cannot enter due to both the sizes of the pores (which are 20,000 times smaller than a water droplet) and the material's extremely low surface tension, which cannot absorb liquid water without tremendous pressure. Kinda cool, right?

Polytetrafluoroethylene is a huge word, but you might have heard it because of its slightly better-known name from the DuPont brand: Teflon. W.L. Gore always tries to improve their products and understands the valuable market share the Gore-Tex brand occupies. They want to do their best to maintain that good reputation. To better achieve that end, the company has strict rules and restrictions for manufacturers that want to use their product. For example, they set rules on face fabrics, interior fabrics, zippers, and, in some cases, applications to help maintain their reputation of “Guaranteed to Keep You Dry.”

Gore-Tex with Paclite technology is now slowly evolving into Gore-Tex PacLite Plus. Its earlier iteration was known as Gore-Tex Paclite, a 2.5 layer fabric with a normal Gore-Tex membrane paired with a proprietary super-thin half layer that completely covers the inside. Gore keeps exact specifications pretty locked up, but it more or less has the same properties as most 2.5 layer models (being lighter, more subtle, and slightly more breathable) but uses Gore-Tex as the waterproof membrane. Gore-Tex PacLite Plus is the next evolution, as it replaces the innermost layer of the older Paclite material entirely and instead textures the inside of that waterproof membrane in such a way to resist dirt and grime while increasing durability.

eVent

eVent is very similar in design to Gore-Tex because it is also an ePTFE based material. It was originally designed for industrial air filters by a company owned by General Electric before the company discovered it would make a fantastic waterproof breathable textile. Like Gore-Tex, eVent uses an external face fabric with a similar polytetrafluoroethylene membrane. The biggest difference is the innermost layer: instead of using a solid material like Gore-Tex, which uses a hydrophobic polyurethane (PU) film on the inside, eVent uses a proprietary coating that protects the individual fibers without clogging the pores. The result is a more breathable ePTFE than Gore-Tex, yet a product that needs to be washed more frequently to maintain better breathability.

Polyester, Polyurethane, or PU Films

Higher-end versions of many of the new wave of PU fabrics are quickly catching up to ePTFE membranes like Gore-Tex and eVent in performance while often offering other unique advantages. In these garments, the PU is the laminate that acts as the waterproof layer sandwiched between the innermost layer of the face fabric. If the PU layer is waterproof, why bother to add the ePTFE layer, you might ask? It's because when laminated to an ePTFE layer, it can be exceptionally thin; without it, it must be thicker to achieve the desired waterproof properties.

Three of the most significant advantages to garments featuring fabric that relies on PU for its waterproofing are that they tend to be lighter, have the potential to be more breathable, and can be constructed with FAR more stretchiness. Jackets and other outerwear featuring Gore-Tex or eVent are much harder to make stretchy. Simply put, even the stretchiest ePTFE fabric is nowhere near as stretchy as the stretchier PU or polyester-based options.

Coated Fabrics

Coated fabrics are often used on price-saving models and are nearly always less breathable and far less long-lasting than the above-listed materials. It's worth repeating that even a coated waterproof and breathable fabric still gets sandwiched inside an exterior and interior fabric. It can be used in outdoor garments using a 2-, 2.5-, or 3-layer construction methods. To be clear, you could have a bomber 3-layer shell jacket that still uses a coated membrane sandwiched inside two other layers that form the backbone of that garment's weather resistance. Coated fabrics like PU laminates can be made with stretchy textiles, allowing garments to have more range of motion.

Durable Water Repellent (DWR)

Durable Water Repellent (DWR) refers exclusively to the chemical treatment that has been applied to the exterior fabric (not the membrane or coated waterproof fabric on the inside) and its performance and job are in resisting (i.e., shedding) and beading up water. The goal of DWR is to help keep the external face fabric from becoming saturated, which negatively affects breathability and gives the user a sensation of dampness in the exposed area due to reduced breathability. All waterproof fabrics feature a DWR, but some DWR is also commonly seen on most water-resistant textiles, including garments like insulated jackets, wind shirts, or softshell pieces. Historically, many companies used fluorocarbons or fluoropolymer chemicals, which were applied and bonded to the outside of the exterior fabric. However, with recent laws requiring the removal of PFCs from materials, PFC-free DWR technologies have now been introduced to offer dirt- and water-repellent impregnation without chemical compounds. All major manufacturers are updating their designs to match.

What is Waterproof?

An easy answer would be “fabric that can't let any water through”; however, the problem is water can have a variable amount of force behind it that directly affects the imperviousness of a given material. For example, even concrete can be cut by highly pressurized water, but despite this, most people still consider concrete a waterproof material. Most rain generates around 2-3 PSI (PSI = pounds per square inch) of force. Rain in a severe storm (with 80+ mph winds found in a hurricane) can produce up to 10 PSI.

Types of Waterproof Jackets

Here at OutdoorGearLab, we divide waterproof/breathable shell jackets into two categories: rain jackets and hardshells. Price and fabric construction distinguish these two categories at the most basic level. Jackets generally cost about $90-$300+ and typically feature 2-2.5 layer construction, while hardshells will set you back $250-$800+ and typically feature three layers. Rain shells will work for downhill skiing but are typically more three-season ready than hardshells, a lighter option perfect for hiking, backpacking, and summertime mountaineering.

Hardshells are typically more feature-rich and offer greater durability in design. As a result, they are usually heavier and less packable. Hardshells are better for activities where durability is more of a factor, like downhill skiing or snowboarding. They will still work for summertime applications but are more likely to be overkill for warmer weather pursuits.

Breathability

Similar to waterproof ratings, breathability has a scale to determine its effectiveness. However, breathability ratings couldn't be less like waterproof ratings where the results of a PSI water test are pretty cut and dry. It's not that the tests that prove how much moisture can pass through a given fabric are useless. Instead, it's a recognition that there are FAR more outside factors influencing the total breathability of a given fabric. Things such as the temperature, humidity, and most of all, pressure. These factors also make the tests super unapplicable to real-world use. To make matters even harder, there are no standardized tests to evaluate the results from brand to brand. While we enjoy seeing manufacturers' product specs and design information, and we always try to keep up with the newest materials that may have been introduced, we also consider these important variables when evaluating all products and carry a lens of skepticism into testing.

Breathability and Layering Appropriately

It's important to remember that every jacket has a maximum moisture that can physically pass through it. Thus, when you're working aerobically, you'll want to do your best to ensure you're wearing the minimal amount of layers you can get away with. We've all soaked a synthetic or wool t-shirt while working hard or hiking uphill, and when you are wearing a rain shell, the body doesn't work any differently.

Air Permeable Materials

Air-permeability is a technical term and a new buzzword in the outdoor industry. It refers to a fabric's ability to consistently let air and moisture pass through it, regardless of pressure and temperature differences. This also means that these garments aren't technically windproof. Not that they feel like a cotton T-shirt on a windy day, but you will chill more quickly when wearing an air-permeable model than a non-air-permeable one.

A common misconception about air-permeable materials is that more moisture can pass through versus non-air permeable fabrics or offer superior breathability overall. Just because a fabric is air permeable doesn't necessarily mean it results in higher performance in these areas. It will always depend on the exact construction of fabric in question, and to some extent the conditions and activity level of the user when assessed. For example, we have tested several air-permeable models that just aren't as breathable as other non-air-permeable ones made of fabrics like eVent and Gore-Tex, at least when a person is exercising and generating heat.

Confused? Here is another way to think of it; air-permeable models offer a steady level of breathability regardless of what the user is doing and the temperature outside. Fabrics like Gore-Tex and eVent vary in how much moisture they allow to move through them based on the pressure difference between the inside and outside of the jacket. Basically, the harder you work, the more heat you generate on the inside, and the colder the temperature is outside, the better such garments will breathe. So the most breathable non-air permeable models (like Gore-Tex Active, Paclite, and eVent) are more breathable if you're hiking when it isn't too warm outside. But once you stop and your body cools off, there's no question that air-permeable fabrics do better.

This means that air permeable models don't require the same heat build-up as non-air permeable models, and they continue to breathe even after their user has cooled off (but might still be wet on the inside). In general, many fabrics that use air-permeable materials tend to be among the most breathable ones, especially the higher-end ones. However, several more budget-priced models are air permeable even if they are not as breathable as classic ePTFE materials like eVent and Gore-Tex.

Ultralight Jackets

Ultralight models are minimally featured bare-bones jackets designed to be as light and compressible as possible. These models skip classic features like hand pockets, hood and hem adjustments, and generally all ventilation features. They excel at activities where saving weight and ensuring a compact packed volume is of the utmost importance. These models are best suited for generally dry pursuits in cool to cold weather or shorter spats of drizzle, like guarding against an occasional afternoon thunderstorm.

The small, featherlight pack size makes these perfect for just-in-case storm protection. They are also easy to toss in your pack, clip to your harness, or stash in your running vest. These models often also have reflective logos and patches, making them great for running and biking.

Depending on where people like to recreate and what they like to do, an ultralight, trimmed-down model might suit some shoppers better than a heavier, fully featured jacket. Most outdoor enthusiasts carry their rain shell 90% more often than they wear it. As a result, all those rad features that seemed sweet in the store only add weight to the bottom of your pack (especially if it's a jacket you rarely actually put on).

Sizing Your Jacket

Consider if you want your rain jacket to fit snugly for more active use or a little loose to allow for layering underneath. A loose-fitting jacket gives you more room for insulation and base layers. But does it perform better one way or the other? A snug-fitting jacket will maximize breathability, which transfers water through the fabric away from your body. Water vapor always wants to move from warm to cool. A snug-fitting jacket will create a more uniform (warm) environment that promotes breathability. A loose-fitting jacket better promotes ventilation. Pit zips, pocket vents, open wrist cuffs are all design elements that help to move more air.

Care & Cleaning of Rain Jackets

A well cared for, clean jacket will function better and last much longer than a dirty, neglected one. First off, be kind to your jacket. Whether you stuff the jacket into its pocket or roll it away into its hood, you will prolong the performance of the DWR treatment if you open it up at the end of your trip rather than storing it wadded up. The less abrasion and abuse your jacket's face fabric receives, the better this will help prolong the DWR and the jacket's ability to shed water.

Eventually, you will want to wash your jacket. Done correctly, washing and drying can miraculously restore DWR and breathability. This shouldn't be underestimated. These jackets can be washed in the washer, although a front-load machine without a center agitator is best. Any fabric with a DWR treatment should be washed in cold or warm water using a small amount of powdered detergent. Find the manufacturer's recommendation on the jacket's label or website, and follow those instructions. Cold water and a delicate cycle is your best bet if you have any doubts. Liquid detergents and fabric softeners should be avoided, as they have components that adhere to the fabric's fibers and encourage the piece to absorb water. Choose a double rinse cycle to remove as much soap residue as possible.

Now you have a clean jacket. Any oils, dirt, grime, soiling, and clogging up the waterproof/breathable layer will have been washed away, and the original breathability should be restored. Next comes the important bit: drying. Hanging or laying your jacket to air dry is the safest technique. A freshly laundered, air dried jacket will sometimes restore a DWR that was previously losing its ability to bead water. Carefully applied heat can also work wonders if cleaning alone doesn't restore the DWR. When trying this technique, a dryer's low heat setting is the place to start.

After enough use, it will always be necessary to reapply a DWR treatment to your jacket's exterior. Spray-on and wash-in treatments are available. Two-layer jackets with a mesh liner should only be treated with a spray-on product; you want the mesh liner to continue absorbing sweat and moving it towards the outside. However, the spray-on or the wash-in option can be appropriate for a 2.5-layer jacket. We prefer spray-on products for more controlled accuracy in application.

Here is the advanced technique for spray-on application. Wash your jacket as described above and let it air dry. Briefly place the jacket in the dryer on low heat, until all the fabric is nice and warm. Remove from the dryer, hang, and immediately spray on your new DWR. Use less spray-on product, and with a hairdryer you've readied on a low setting, accelerate the drying of the new DWR. This technique serves to both restore the original DWR that remains on the jacket and maximize the bonding of the new polymers you are applying. Nikwax and Granger both produce a full line of fabric treatments, including spray-on and wash-in varieties.

Hood Design and Applications

You should consider your intended activities with your jacket and consider what you need from its hood. Do you need it to fit over a climbing or bike helmet? Or is a helmet a rare enough occurrence that you can just tuck it underneath when it comes up? How important is good peripheral vision? None of the jackets we tested were awful, but there's no doubt that some score higher for their hood designs.

We'd recommend an over-the-hood design to any climbers or cyclists reading this. While you can wear a given model's hood underneath your helmet in a pinch, a helmet-specific design might be superior for regular use. A hood is far easier to flip on and off if it goes over the top of your helmet rather than when trapped underneath it. Besides being less convenient to put on and off, when you wear your hood underneath your helmet, it becomes warmer and can be less comfortable than when you wear it outside.

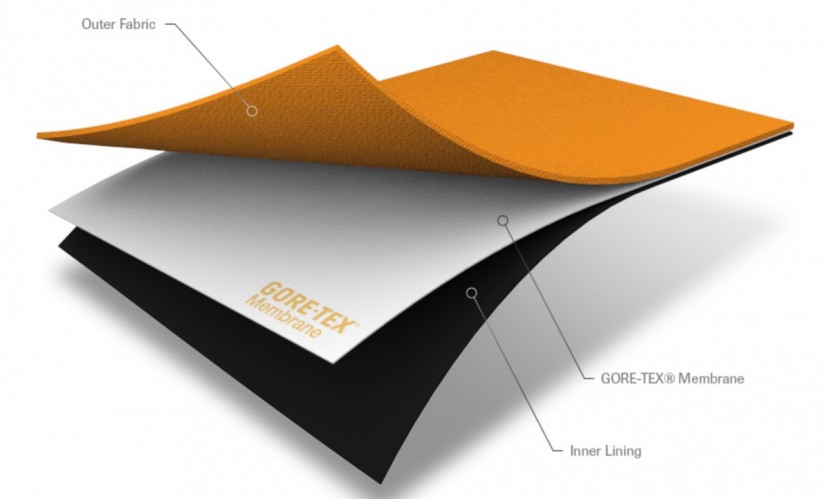

History of Waterproof Breathable fabrics

The world changed for waterproof clothing in 1976 when W.L. Gore and Associates introduced Gore-Tex fabrics to the market. Gore discovered and patented the process for creating ePTFE, or expanded Polytetrafluoroethylene. This thin film contains millions of small pores, too small for liquid water, but large enough for water vapor to pass through. Laminate this thin membrane to a synthetic face fabric and voila; the first waterproof and breathable fabrics. Today's waterproof/breathable layered fabrics include laminated face fabrics to those with membranes like Gore-Tex, while others are built using face fabrics treated with an additional protective coating.

Gore-Tex rainwear quickly conquered the market or, in one sense, created the waterproof/breathable market. Competing waterproof fabrics coated with Polyurethane (PU) or Polyvinylchloride (PVC) couldn't compete. The first Gore-Tex fabrics were 2-layer construction; the ePTFE membrane laminated to a nylon or polyester face fabric and a mesh or thin fabric liner hung inside this layered fabric to protect it and provide comfort next to your skin. But Gore quickly discovered that the ePTFE membrane's pores could easily become clogged with oils and dirt. So, the company added another layer to the laminated sandwich, covering the ePTFE membrane with an oil-resistant PU layer. This PU layer protects the pores from contamination and stops all airflow through the membrane's pores. Three-layer construction was the next big advance, and mesh or scrim was laminated to the fabric's innermost layer, which protects the membrane and provides a better water transfer through to the outside. As the “light is right” ethos took over the outdoor world in the 90s, 2.5-layer technology also did. Instead of laminated mesh, this construction incorporates a texturized “half layer” printed on the inner face of the layered sandwich.

So does traditional Gore-Tex breathe? No, in the sense that air does not pass through. Yes, in the sense that liquid water passes through the innermost PU layer and then is wicked to the face fabric through the ePTFE's pores, where it evaporates. This wicking process works best with a large temperature gradient. Water always wants to move from warmer to colder zones. Fabric that does a great job “breathing” when it's cool outside will not wick nearly as much sweat away from your body when it's hot out.

Gore's original patents for ePTFE expired in the mid-90s, and competitors, many of whom had been developing PU membranes and advanced PU coatings, began experimenting with PTFE technology. Options multiplied for manufacturers of outdoor performance clothing, but Gore-Tex has maintained its dominating market share for high-end waterproof/breathable fabrics. Polartec NeoShell and eVent are the latest ePTFE laminates. None of these technologies uses a PU layer, and as a result, both are air permeable. High performing PU membranes are also popular today; examples include Patagonia's H2No and Marmot's air permeable NanoPro laminate. As these newer, truly breathable, or air permeable membranes gain traction, Gore has also gotten on board. Their latest version of Gore-Tex Pro is the first to eliminate the PU layer, creating the first air permeable Gore-Tex fabric. In our review of hardshell jackets, you'll find jackets intended for serious mountain activities, constructed with these advanced three-layer laminates.

Further Reading

Here is a good summary of many of the top of the line waterproof/breathable fabrics. Marmot's new NanoPro fabrics are rightly garnering much attention. Here is a good article comparing NanoPro to the new air-permeable Gore-Tex Pro. For those of you interested in the history of Gore-Tex, and how W.L. Gore revolutionized the outerwear market, and perhaps discouraged further innovation, read Insane in the Membraine.