Almost all styles of climbing (save bouldering and free soloing) require carabiners. If you are looking to buy individual ones you are most likely a traditional climber, or hoping to become one. If you only sport climb, then you'll want to have a look at our locking carabiner advice guides instead, as well as our quickdraw review. While carabiners might not seem that expensive when purchased individually ($6-15), you end up needing a lot of them when traditional climbing and twenty can cost you as much or more than a rope. They do tend to have a long lifespan compared to soft goods like a harness or rope, so make sure you purchase something you like as you might be using it for the next ten plus years.

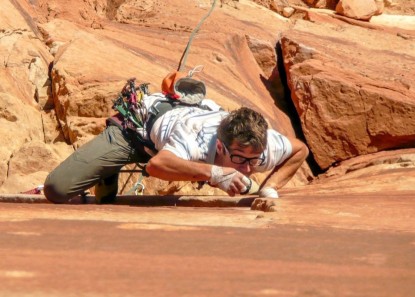

When buying and organizing your first rack of gear, it can be tempting to buy twenty or more of the same one, but if you look at most peoples' racks they tend to have a hodgepodge of gear, and there is nothing wrong with that either. You may prefer one style for certain applications, like racking your cams, and other styles for racking your nuts or for “alpine” draws. They often go missing, and it's easy to acquire them accidentally from your friend's rack or by snagging someone else's “bail-biner.” If, after reading this article, you are still not settled on which models to buy, you can create your own mini-review setup. Choose a few products that pique your interest or feel good in your hand in the store. Buy one or two of each and start using them. Once you've settled on your personal favorite, you can expand your rack with those, and keep the others for lesser jobs like carrying webbing or your nut tool.

In this article, we will go over the types of metal and forging methods used, the different gates you can choose from, and what all those strength ratings actually mean. We'll also discuss weight and longevity. To learn more about the products we tested, be sure to check out our full review.

Construction

Metal

Climbing carabiners are manufactured out of stainless steel or aluminum. Steel ones are stronger and more durable than aluminum ones, but they also weigh twice as much (or more!) and are mainly used for fixed draws or anchors. All of the products that we tested in this review are made of aluminum.

AnodizingAluminum carabiners are anodized to increase their resistance to corrosion and to dye them different colors. The anodized layer is microscopically thin and doesn't increase the strength of the aluminum, but it does prevent the metal from deteriorating, particularly when/if the user exposes it to salty water and air. The anodized layer will wear off the rope bearing surface fairly quickly, but it still protects the rest of it. Even if yours are anodized, if they are ever exposed to salt water be sure to wash them thoroughly afterward as it will quickly deteriorate the metal.

Unless you regularly climb on sea cliffs, anodizing is more of a cosmetic concern and also a convenience to you. Manufacturers dye the same models in multiple colors and sell them as “rack packs” so that you can color code them to your camming devices. This might seem silly to you - in fact, the first time our main reviewer saw the Black Diamond Neutrino rack pack over a decade ago, she laughed and might have made some comments along the lines of “who needs that anyway?” The laughing lasted all of about two pitches once she started using them, as she quickly realized that this was a huge step forward for trad climbers. No more fumbling on your harness or gear sling looking for the right piece, and re-racking after a pitch is a breeze. Fifteen years later, and she wouldn't consider racking any other way.

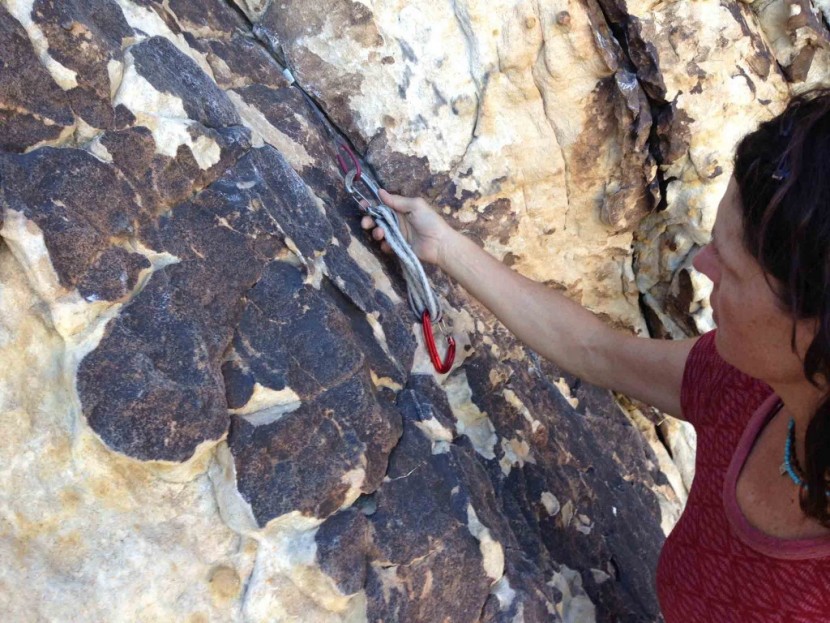

Another advantage to anodizing is that you can have one color for the top of a quickdraw or alpine draw and another color for the bottom. If you buy a preassembled draw they usually come this way already, but when setting up a rack of “alpine” or “extendable” draws (two carabiners on a tripled-up shoulder length sling) you should also do this, because the steel of a bolt, piton or even a nut wire will quickly gouge the soft aluminum. If the rope bearing surface does get gouged, there's a possibility that it can snag the sheath of your rope and in extreme cases lead to rope failure. As an example, the Mad Rock Ultra Light Wire comes in red and silver, so you can easily distinguish which side is for clipping gear and which side is for the rope.

Hot-forged vs. Cold-forged

Cold forging is the original method of making carabiners whereby the rod of aluminum is bent into the desired shape and then stamped in a die at room temperature. In the hot forging process, the rod and forge dies are heated before stamping, which typically allows a manufacturer to create a lighter product with a more intricate design. If you compare a cold-forged vs. a hot-forged model, it is easy to tell which is hot-forged as it will have a more sculpted look. I-beam or cut-out spines can be created with both processes. In this review, the Wild Country Helium, Mad Rock Ultra Light, and the Black Diamond Oz are hot-forged.

CAMP uses only cold forging for their CAMP Photon Wire and Nano 22 models because they feel it results in fewer irregularities in their product and it's more reliable than hot forging. A climber might never actually notice the difference between the two methods. Most hot-forged models are more expensive, except that our Best Buy winning Mad Rock Ultra Light ($6) is actually hot forged. And while our Top Pick for Lightweight Black Diamond Oz is hot-forged, the even lighter Nano 22 is not.

In perusing other reviews and message boards, we noticed some concern about hot-forged models being less durable. People are grumbling that their gear used to last ten years and is now wearing out in one or two. This is not necessarily a result of the forging method but of how much metal is used in the process. A lighter weight model, hot or cold forged, will have less material overall, specifically on the rope bearing surface, which leads to quicker grooving. If you are more concerned with the longevity over the weight, choose a big and beefy model like the Petzl Ange L, which has a large rope-bearing surface and should last a while.

Gates

Improving gate technology has always been a top engineering concern for manufacturers, and climbers. The enhanced designs of the last few decades have created safer, lighter, and snag-free gates. The two main types of gates are solid or bar stock gates, and wiregates. Note that we tested only wiregate models in this review, as they are lighter and better suited to traditional climbing, but cover both in our quickdraw review.

Solid

Today's solid gates are much improved from older models. Virtually all solid gates on the market today are “keylock.” Instead of a pin on the end of the gate that latches on a notch in the nose, now the nose itself latches on a groove in the barrel of the gate. Since it does not have that notch in the nose, a keylock design won't snag on your rope when unclipping or catch your gear or bolt. One rare but dangerous scenario that can occur with a notched nose is a “nose clip.” This occurs when a carabiner isn't clipped on the bolt properly to begin with, or if it shifts as the climber moves past it, leaving the notch hooked precariously on the lip of the bolt. While rare, this can result in gear failure at loads of less than 10% of the closed gate strength (<2 kN.) This small amount of force is easily reached in a fall or even a bounce test. In part to help avoid this scenario, most sport-climbing specific quickdraws now have keylock bar gates at least on the top, and often on the bottom too.

WireWiregates are over 20 years old now and have become the preferred type of gate for traditional climbing. The single loop of metal weighs less than the bar, pin, and spring of a solid gate, and can shave 7 grams or more off the total weight. These weight savings are crucial, particularly since you carry a lot of carabiners when trad climbing - and because your camming devices already weigh a lot. Another advantage of the wiregate is that it's less prone to icing up than a solid gate in cold conditions, and they are the preferred model for ice and alpine climbing. Since the wire is much narrower than the bar, they also have a larger gate opening than a similarly sized solid gate model, and a wider opening is also useful when climbing with gloves on or when using multiple ropes.

Wiregates are less prone to “gate flutter,” a rare but serious issue. When a carabiner catches a fall, the forces generated cause the gate to vibrate. The more mass in the gate, the more vibration, and the gate itself can flutter open and closed. The strength of a carabiner with an open gate is roughly 2/3 of its closed gated strength, anywhere from 7 kN to 10 kN. This level of force can be achieved in a real-life fall and could result in the piece failing. While this is a rare phenomenon overall, it is even rarer in wiregates than solid ones.

The downside to a wiregate is that on most models there is still an exposed notch in the nose that the wire latches on, just like the old-style solid gates. More and more companies are devising ways to eliminate this notch, effectively creating wiregate/keylock hybrids, which is the best of both worlds. Wild Country has buried the notch in the nose of its Helium model, and Black Diamond has developed a stainless steel wire hood that is swaged around the notch of the Oz , protecting the notch from catching on anything. Petzl uses a single wiregate on its Ange model that fits in a slot similar to keylocking bar gates. Whatever the method, the advantages are real. In addition to reducing snags, they also protect the wiregate from scraping open against the rock. We should note, however, that it can be challenging to fit these noses in tight situations, like bolts stuffed with rappel slings or pitons with narrow openings.

Bent vs. Straight

Both solid and wiregates can be straight or bent. Most climbers tend to find bent gates easier to clip than straight gates, and that's why you'll find them on the rope end of a quickdraw, but according to Petzl, there is a higher risk that the rope will become unclipped from a bent gate model in a fall. Check out their great info-graphic for tips on how to avoid dangerous clipping situations.

Tension

The tension on a gate determines the clipping action: fast and snappy, stiff and slow, or soft and easy. This is often a personal preference, though it is very important that there is some spring tension that returns the gate to its fully closed position. In solid gates, that tension is created by a spring in the barrel of the gate, and in wiregates, it's created by the pivoting of the wire itself. That tension can decrease over time, due to the build-up of dirt or grime, or due to corrosion. An open gate reduces the strength by roughly 2/3rds (see Strength section below) and creates the potential for the rope to come unclipped or the carabiner to break in a fall. If your gates become “manual” and no longer close on their own, wash them according to the manufacturer's instructions and lubricate the joints.

If, after a thorough cleaning and lubricating a gate still does not close on its own, you must retire that piece. Even if you manually close it back after clipping, the gate can scrape against the rock back into a dangerous open configuration.

Strength

Most climbing gear is CE certified. This certification is from the European Committee for Standardization (CEN), which requires gear to meet certain standards to be sold in the EU. Even though the U.S. has no set standards for climbing gear, most American manufacturers build to this specification and are CE certified in order to sell their products overseas. All of the models we tested in this review are CE certified. To check if your own gear is, look for a CE and four numbers stamped or printed on the side. If it's not, as long as it meets the minimum strength requirements below (also stamped or printed on the side) it should be alright.

The minimum CE requirements for a non-locking carabiner are:Major axis - 20kN (along the spine)

Gate open - 7kN (along the spine but with an open gate)

Minor axis - 7kN (cross-loaded spine to gate)

Many products have even stronger ratings within the following ranges, particularly if they are full sized and heavier:Major axis - 23-25kN

Gate open - 8-10kN

Minor axis - 8kN

How much should strength influence your purchase? A lot depends on the type of climbing you'll be doing most. A stronger model with a large major axis strength is preferred for sport climbing where you are more likely to take repeated falls on your gear. When alpine or moderate trad climbing, you can use a lighter and lower strength rated model, like the Black Diamond Oz or CAMP Nano 22, but be sure to inspect your gear thoroughly after a major fall, as it can become warped and unusable. Check out this article from Black Diamond's Quality Control Lab, to learn more about the tests they perform on products of different strengths.

You should also consider the gate open strength of your gear as there are many scenarios that can accidentally cause your gates to open slightly, or fully, and an open gate strength of 9 or 10kN is that much safer than 7kN.

Size

These products come in many different sizes, from a standard full-size option (roughly 4 inches long and 2.5 inches wide) to “keychain” size (3.5 x 2), and many options in between. While this might not seem like a big variance on paper, our testers noticed a big difference between them in practice. Full-size models are generally easier to clip and handle, particularly with gloves on. If you do any type of cold weather or big wall climbing, make sure you purchase a full-size model. You'll do well with larger sized ones for sport climbing, where you want your clips to be fast and easy. On the flip side, when choosing a product to rack your cams, you might prefer something that is a little smaller and more narrow, like the Trango Phase or Black Diamond Neutrino. They'll take up less space on your harness or gear sling, and are lighter than a full-size option. If you have tiny hands or are looking for the lightest model possible, then a “keychain” size one, like the Metolius FS Mini II or CAMP Nano 22, are good options.

Another consideration is the rope bearing surface. When the rope catches your fall, it is bent around the basket of the carabiner. The wider the basket, the gentler the bend on the rope and the less impact it has on it. So, for sport climbing, where you might be taking repeated falls on the rope in the same place, a wider rope bearing radius is preferred. Same is true for setting up a top rope anchor.

Weight & Types of Climbing

The weight between products can vary greatly, from 19 grams (the lightest full-strength option - made by Edelrid) to 64 grams for a full size oval. You'll want to closely consider the weight of your gear if you do any sort of multi-pitch climbing, be it sport or trad, are hiking your gear long distances into the backcountry or trying to climb light and fast on a big wall. While a few grams here or there might not seem like much difference either way, remember that between your cams and draws, a full rack of gear will have around 40 carabiners on it, and those few grams will quickly add up to ounces and even pounds saved.

Lifespan

The lifespan of your gear will be determined by the amount of use it gets, the way you care for it, and its exposure to corrosive elements. Our main tester's entire set of anodized carabiners had to be replaced after a season of climbing in Thailand thanks to the corrosive effects of the sea and uniquely active limestone (she might not have washed them after getting dunked on a rappel off Ao Nang Tower either.) Once she learned how to care for her gear, she now has some that are more than ten years old and still perfectly serviceable.

Rope wear is one of the main ways they will wear out, particularly when sport climbing. Repeated lowering and top-roping causes small amounts of metal to wear away, and eventually, a pronounced groove will develop. This is different from the intentional groove that many baskets have across the rope bearing surface. This slight depression is there to guide the rope as close to its main (and strongest) axis as possible. According to Petzl, any groove caused by wear more than 1mm deep is a warrant for concern since sharp edges can start to form on the edge of the rope bearing surface; edges like these can sever your rope in a fall. Black Diamond has conducted several tests about this at their Quality Control lab - you can read more about them here and here.

To increase the longevity of your gear, inspect it regularly, particularly if it's been dropped from a height or caught a severe fall, and clean/lubricate any sticky pieces. Petzl's

inspection procedures document has more detailed information on this, including recommendations on when to retire pieces. No one likes to throw away gear that might still be ok, but in a sport like rock climbing, where your life is literally on the line, you're better off playing it safe and spending a few dollars on some new gear.

Now that you're armed with just about everything you need to know about buying the right product be sure to check out our full review, to see how each model scored in our side-by-side comparison testing.